Donostia / San Sebastián during the Belle Époque, two centuries of tourism

- Culture

- 2024 Apr 10

Did you know that in the mid-19th century, one vote was all it took to decide that the city of Donostia was to be built as an attractive tourist destination instead of a port for industrial activity and trade?

A decision which shaped its development and turned San Sebastián into a beautiful bustling city with pleasant walks, infrastructures and a cultural agenda similar to major European cities.

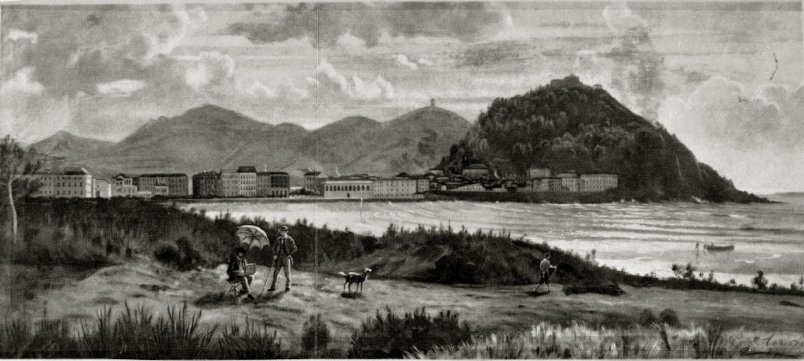

©Pascual Marín.(Pintura de Eugenio Arruti). Playa de Gros y Monte Urgull desde Ulía,1865.Kutxa Fototeka

©Pascual Marín.(Pintura de Eugenio Arruti). Playa de Gros y Monte Urgull desde Ulía,1865.Kutxa Fototeka

Tourism in Donostia / San Sebastián is not the outcome of a recent boom, as may have been the case in other cities. For an understanding of the history of tourism in Donostia / San Sebastián, we could go back to the late 18th century, when sea-bathing became popular in certain parts of Europe, and the belief emerged that the sea was beneficial to human health and could cure illnesses such as arthritis, leprosy, tuberculosis and all kinds of ailments: "each treatment must be rounded off with cold sea-bathing … This brings about the perfect cure" (Richard Russell, 1750).

©Cesáreo Castilla Moleda.Vista de gente en la playa de la Concha. Pasarela de bajada al agua de la caseta real. Kutxa Fototeka

©Cesáreo Castilla Moleda.Vista de gente en la playa de la Concha. Pasarela de bajada al agua de la caseta real. Kutxa Fototeka

San Sebastián did not forgo this trend, and was frequented by many families, chiefly from Madrid, fleeing the heat of the capital in search of a better climate and sea-bathing. At that time the usual practice was to stay at private houses, where rooms were let as a way of helping many people in Donostia make ends meet.

San Sebastián and the first royal visits

The first royal visit to San Sebastián was in 1830, when the city played host to the "infante" Francisco de Paula, brother of Fernando VII, and his wife Luisa Carlota, queen María Cristina's sister.

©Litografía de G.Carpenter. Caseta de baños construída para la reina Isabel II en la playa de San Sebastián,1845.

©Litografía de G.Carpenter. Caseta de baños construída para la reina Isabel II en la playa de San Sebastián,1845.

Queen Isabel II made her first visit in 1845 as a teenager with herpes, whose doctor had prescribed "wave-bathing". Isabel II's continued presence served as a genuine megaphone to publicise the city, and many other visitors arrived from Madrid, but also from other countries, mainly the United Kingdom and France. Nor should it be forgotten that Biarritz was close by, and at the time this was a considerable magnet for European aristocrats and royalty.

Boulevaristas (tertiary tourist city) vs. antiboulevaristas (a port for industrial activity and trade)

1863 was an important year in the city's history. This was when permission was finally granted to demolish San Sebastián's walls, and "bidding terms " were published for an extension of the city. The winning design was by Antonio Cortázar, whose agreement with the city authorities compelled his offer to include certain parts of the design by the runner-up, Martín Saracíbar, such as a tree-lined avenue at the point where the old and new parts of the city converged, as an open leafy space. Cortázar's final plans, however, did not include the avenue, and this led to a major controversy concerning the model to be used for the city.

©Colección Foto Marín.Vistas del Puerto.Kutxa Fototeka

©Colección Foto Marín.Vistas del Puerto.Kutxa Fototeka

The antiboulevaristas wanted a trading city model, a posture upheld by Cortázar, focusing on growth of the city with the help of the railway and development of trading, with a large goods harbour. They wanted a railway line to connect the train station to San Sebastián harbour, with large goods warehouses around the port. Tourism was seen as a secondary concern.

Hauser y Menet. Portalón. Al fondo las viviendas de la calle Mari y la torre de la Iglesia Santa María.

Hauser y Menet. Portalón. Al fondo las viviendas de la calle Mari y la torre de la Iglesia Santa María.

The boulevaristas called for a tertiary tourist city, which ought to focus on aesthetic criteria in order to build a beautiful pleasant city for visitors. They saw tourism as the primary economic driver, and called for a large tree-lined avenue of greenery (Alameda del Boulevard), in addition to other open spaces, promenades and gardens to create an attractive city of leisure.

©Ricardo Martín. Alameda del Boulevard,1923. Kutxa Fototeka

©Ricardo Martín. Alameda del Boulevard,1923. Kutxa Fototeka

After two years of lively argument between boulevaristas and antiboulevaristas, a vote on the model to be used for the city was taken at a plenary session of the town hall in May 1865, resulting in a 7-7 stalemate among councillors. Faced with this situation, the mayor, Tadeo Ruiz de Ogarrio, made use of his casting vote and tipped the balance in favour of the boulevaristas.

The victory of the boulevaristas led to alterations in Cortázar's design, with an avenue to serve as a meeting point and an itinerary for walks. Moreover, with the advent of the railway and rapid communication between San Sebastián and the surrounding area, Pasajes harbour was conceived as a viable alternative, and became the major port of San Sebastián and Gipuzkoa.

©Paco Marí.Puerto de Pasajes.Kutxa Fototeka

©Paco Marí.Puerto de Pasajes.Kutxa Fototeka

San Sebastián, therefore, was now moving towards an extremely well defined city model. A modern city with the necessary infrastructures and attractions to bring in visitors with high spending power who would generate profits for the city, with an attempt to lay on more distractions in a bid to lengthen their stays there. Following the demolition of the city walls, all activity in San Sebastián concentrated on making it one of Europe's major cities.

©Pascual Marín. Vista del Casino de San Sebastián y de los jardines de Alderdi-Eder. Kutxa Fototeka.

©Pascual Marín. Vista del Casino de San Sebastián y de los jardines de Alderdi-Eder. Kutxa Fototeka.

It was for this reason that, between the decades of 1870 and 1880, the city created its week of fiestas, "Semana Grande", the Atotxa bullring, the first regattas in La Concha bay, San Sebastián's Gran Casino, the Hotel Continental (with the first lift) etc.

©Ricardo Martín.Francisco Laboa y la tripulación de la trainera de Pasai Donibane en la bahía de la Concha. Kutxa Fototeka.

©Ricardo Martín.Francisco Laboa y la tripulación de la trainera de Pasai Donibane en la bahía de la Concha. Kutxa Fototeka.

Queen María Cristina summers in San Sebastián. New infrastructures.

©Colección Foto Marín.El rey Alfonso en el embarcadero del Náutico,1920.Kutxa Fototeka

©Colección Foto Marín.El rey Alfonso en el embarcadero del Náutico,1920.Kutxa Fototeka

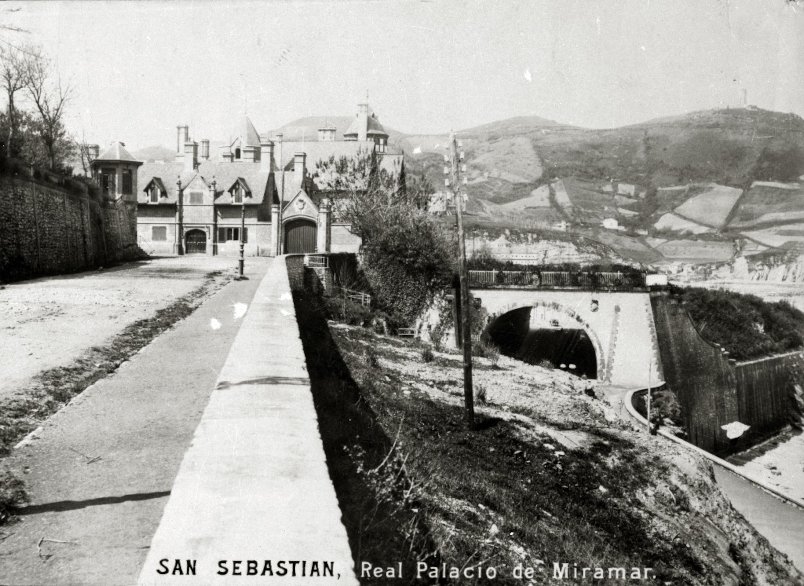

The queen regent María Cristina, the widow of Alfonso XII, picked San Sebastián as her summer spot for more than 40 years, from 1887 to 1929, staying at first in Palacio de Aiete and later at Palacio Miramar, which was built at her request in 1893.

©Foto Marín.Palacio de Miramar recién construido y túnel de Ondarreta vistos desde Miraconcha. Al fondo, el monte Igeldo,19 Centuria.Kutxa Fototeka

©Foto Marín.Palacio de Miramar recién construido y túnel de Ondarreta vistos desde Miraconcha. Al fondo, el monte Igeldo,19 Centuria.Kutxa Fototeka

In 1887, La Concha was given the title of "Royal" beach and an enormous wooden hut was built there, to be replaced in 1912 by the new “La Perla del Océano” spa, held to be one of the world's most beautiful by communication media at the time.Summer holidays for therapy and sea-bathing, however, eventually showed signs of a wane, and the focus shifted to entertainment and distractions. The city therefore introduced a number of infrastructures which have left a deep imprint on its layout.

©Ricardo Martín.San Sebastián. Playa de la Concha. La Perla. 1915. Kutxa Fototeka

©Ricardo Martín.San Sebastián. Playa de la Concha. La Perla. 1915. Kutxa Fototeka

By 1907 San Sebastián, with a population of 44,454, had notched up 1.3 million overnight stays, not so far behind the 1.7 million overnight stays nowadays.

©Ricardo Martín. Personas en la playa de La Concha de San Sebastián,1916. Kutxa Fototeka

©Ricardo Martín. Personas en la playa de La Concha de San Sebastián,1916. Kutxa Fototeka

In July 1912 Donostia's finest “Belle Époque” era emerged, with an incredible succession of inaugurations within a very short space of time: the La Perla spa, Hotel María Cristina, the Victoria Eugenia Theatre and the funicular railway up to Monte Igueldo (which had a casino-restaurant-theatre).

©Hotel María Cristina.Kutxa Fototeka

©Hotel María Cristina.Kutxa Fototeka

The first years of the 20th century also witnessed the inauguration of the Lasarte horse-racing track, the new Kursaal casino, the Lasarte motor racing circuit etc. The Gran Casino, which was visited by historical personages such as Maurice Ravel, Leon Trotsky, the shah of Persia and Mata Hari, became the city's driving force, and sponsored the construction of San Sebastián's Paseo Nuevo promenade in a bid to bring in more visitors.

©Ricardo Martín.San Sebastián vistas.Puente de la Zurriola y edificio del Gran Kursaal,1923.Kutxa Fototeka

©Ricardo Martín.San Sebastián vistas.Puente de la Zurriola y edificio del Gran Kursaal,1923.Kutxa Fototeka

San Sebastián began to appear in major international guides as a tourism reference.

San Sebastián reinvents itself: a more popular kind of tourism

In 1924, Primo de Rivera's dictatorship banned gambling, and the casinos closed down. In this situation, San Sebastián reinvented itself to concentrate on a more popular kind of tourism. In 1927 the Town Hall took up the tourism initiative, beach huts were built, Monte Igueldo was turned into an amusement park, and the Palacio del Mar (Aquarium), Club Naútico etc. were opened.

©Pascual Marín.Celebración de pruebas de natación y salto de trampolín en el puerto de San Sebastián.Kutxa Fototeka

©Pascual Marín.Celebración de pruebas de natación y salto de trampolín en el puerto de San Sebastián.Kutxa Fototeka

In 1929 the city had 40 hotels, 13 hostels, 100 guest houses, and more than 1,000 flats and villas let out to visitors (some 20,000 beds for tourists in a city with a population of 78,000).